Tibor Zalán

Musings upon the Fragments of an Oeuvre

1.

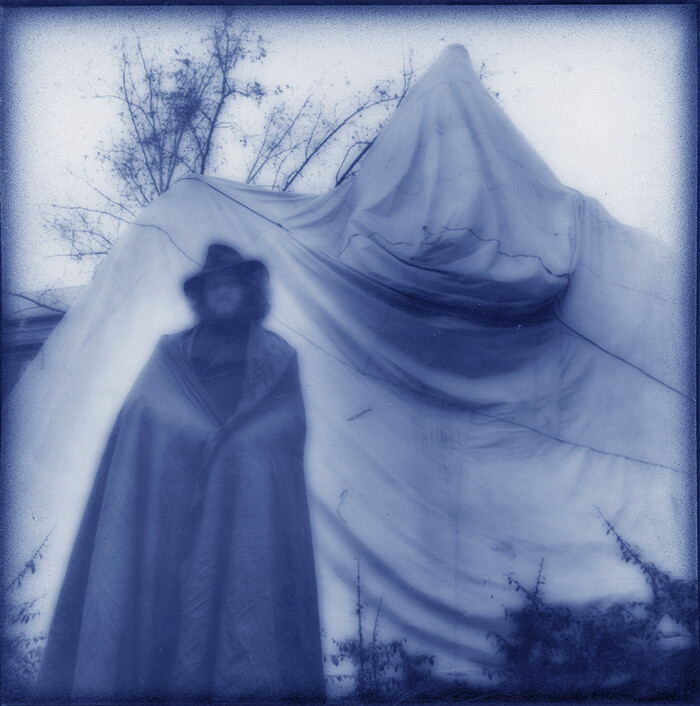

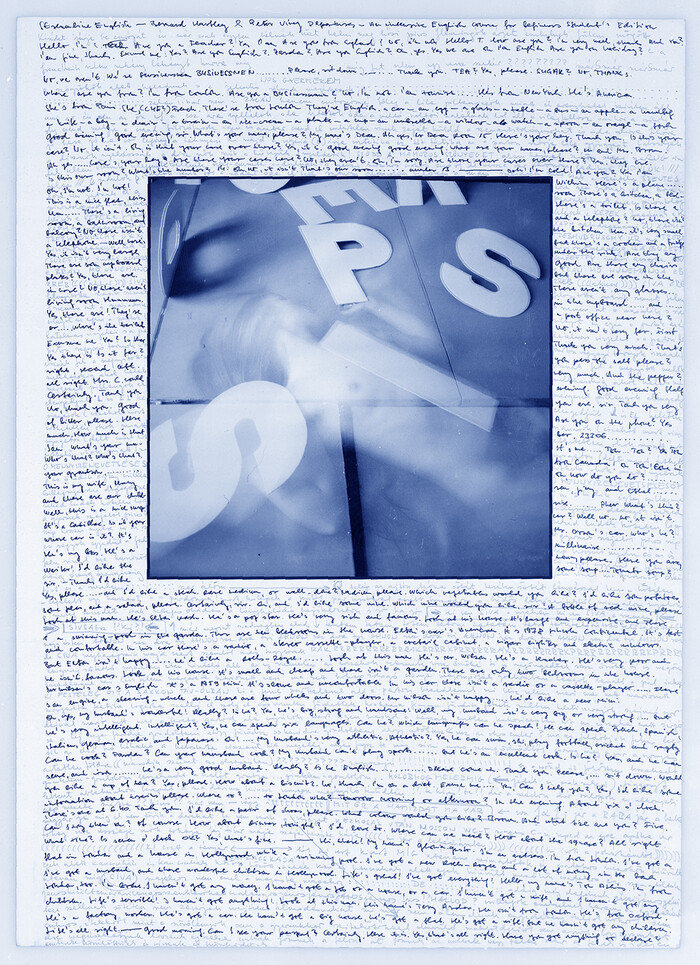

Photography is the molding of light, the process of making light into picture, the transfer of forms drawn by the light in the space around us to the sensitive recesses of the camera, or in most cases today, into digital files. Light is the criterion of the objects’ form of existence. Visibility is the criterion of existence that can be realized only by light. What cannot be seen can also exist, however, but not for the world to see, but only for its own sake. The so-called self-existence can never be the same as the existence in our world. In fact, the motion of the objects is the motion of the light in the world. Furthermore, light is the condition of our perception of movement. However, light itself is immobile. As immobile as the photograph created by capturing the immobile light. Immobility, what can record both immobility and the suggestion of motion. So, the photograph captures the immobility of light as well as the movement of light. Movement cannot be captured, only the suggestion of movement that is captured. From here it takes only one step to declare that the world is in fact immobile: the movement in it is the light’s form of existence that we perceive as reality. However, reality does not exist, only its imagination. Therefore, the photograph is the image of the imagination. If I want to believe, reality does not exist, but the photograph does in the range of existence, ergo it is an authentic form of existence, contrary to the everyday seem-to-be existence that is only the suggestion of the static or dynamic nature of light. This notion or a notion like this has set off László Török on his way, where he firstly deals with the stages of installation, then transparency. All in all, it is not impossible that I’m wrong, of course.

(first digression)

When I first met László Török, he was an artist made. He had a name. The Török – turned after him everybody at once in the Café Hungária –, the one who received the Grand Prix of the Word Press Photo. A lean figure with a moustache that dribbled down even then, clad in black even then, however, with a crisp white shirt at that time: exactly as how I imagined an artist at the time, exactly as how artists imagined themselves at the time. He was not a member of our age-group, but gladly spent time with us, too. Jenô Balaskó was the best-suited friend for him based on age, but he also liked József Szervác, Károly Szikszai, Erzsébet Tóth, Gábor Cziprián Csajka, and Károly Bari, too, who was not a member of our circle. They have all become his „models“ – or, more accurately, the objects of his installations. He forged a closer working relationship with only me, I believe: I cannot say why he chose me from the up-and-coming talented young poets and writers at that time. Maybe he felt that we shared the same worldview. Maybe it is the fact that I too didn’t believe that the present can be captured, only the past and the future exist. Maybe, because I was or could be a trusted colleague despite my bohemian lifestyle for a determined span of time of his artistic periods. An inspired muse.

Török was an essential participant of my first major happening: apart from us, actor Zoltán Nagy and musician László Sáry took part in the theatrical improvisations of my long avant-garde free verse titled Az ének a napon felejtett Hintalóért (Song for the Rocking Horse that Has Been Forgotten in the Sun). The installations on the „stage“ were made by Török: apart from the huge pictures hung from the ceiling (which were beaten into pulp with boxing gloves during the performance by Török himself), he dreamed up a two-litre soda-water siphon covered in black baize containing spritzer stood on the small table in front of me accompanied by a quite big, also black glass from which I could drink the spritzer to my heart’s content. This all seems to be unrealistic from the here and now, but if I consider it more carefully, our happening was one of Török’ installations of reality. I cannot say if there were any photographs taken during the séance. If the answer is yes, I may prove what I’m wondering about now.

2.

Presumably, it wasn’t the famous, internationally acclaimed piece of art called Család (Family) that started Török’s career, but it is indubitable that this photograph was the first that was widely noticed. Naturally, it is staged, it is a composition. A family is sitting on this photograph, their clothing, and even their stance and countenance suggest that they are the member of the middle-class of the sixties, in a very common setting that was typical at that time. The one thing that makes this photo more than a parody is the fact that the girl sitting in the middle is naked, which should be scandalous, but it is not. Nudity has a special meaning here: it proves that a creature exists in this small community that is intact, not broken, not corrupted, not socialised (either in clothing or in effect), who can dress up (or down) at her heart’s content – however, her milieu suggest that it is not possible, her only choice is the uniformity, and in this context nudity also symbolises the denudement of the victim. The world is such, suggests Török through his artwork, and not as it wants to be perceived: if it were, the girl wore a dress, the same organized middle-class garment as the others did. This is where we can capture the essence and importance of staging in Török’s first big period of photography. (Naturally, this statement is quite inaccurate, since staging is still a major organizing tool of his pictures. We must refine this periodization: during this stage of his artistic activity, staging was the objective of organizing the semblance into reality, meanwhile during his second period this kind of staging shifted to transparency.) His first book was titled Módosulások (Alterations), and this title suggests the importance and central role of displacement. One of his frequent photo-poetic tools is the repetition in the picture, when he photographs a landscape or a staged studio installation, then, after placing a female nude inside (standing or lying), he takes a picture again. The interpretation of the shift between the two picture becomes the essence of the artwork. Female nudeness accompanies Török’s whole picture-poetry. (I intentionally used the word poetry, because I regard him as a poet, who is always striving to capture the inexpressible, but has only the visuals that seem to be graspable – as poets have the vocabulary – to express what can be captured only at the level of senses. In other words: many of his pictorial references prove that his intellectual existence can be defined in extension of the poetic material.) Here, nudity cannot be compared to the existence of nude images that evidently and willingly suggest erotic contents: in Török’s case corporeality is eliminated because of the objectification of the spectacle of corporeality. The female nude is the part of the semeiology and not the point of capturing the effect. Nude images are the tools of achieving arousal: for Török, female nudes are one of the few tools he can use on a photograph, like a piece of wood, a pane of glass, a fractured block of marble.

(second digression)

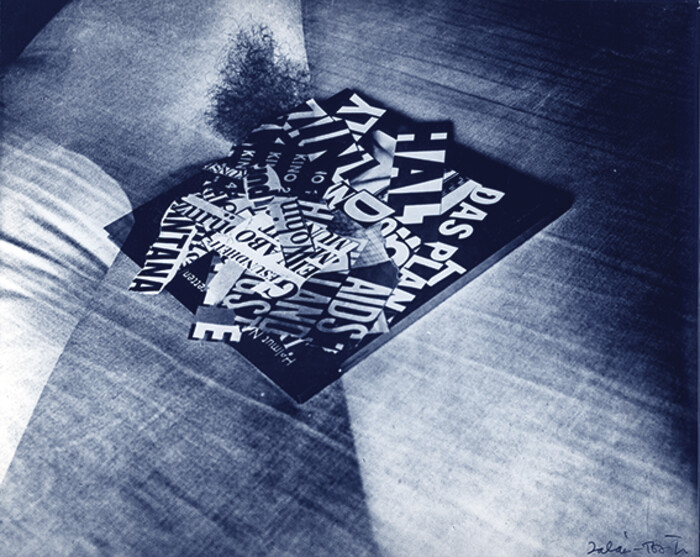

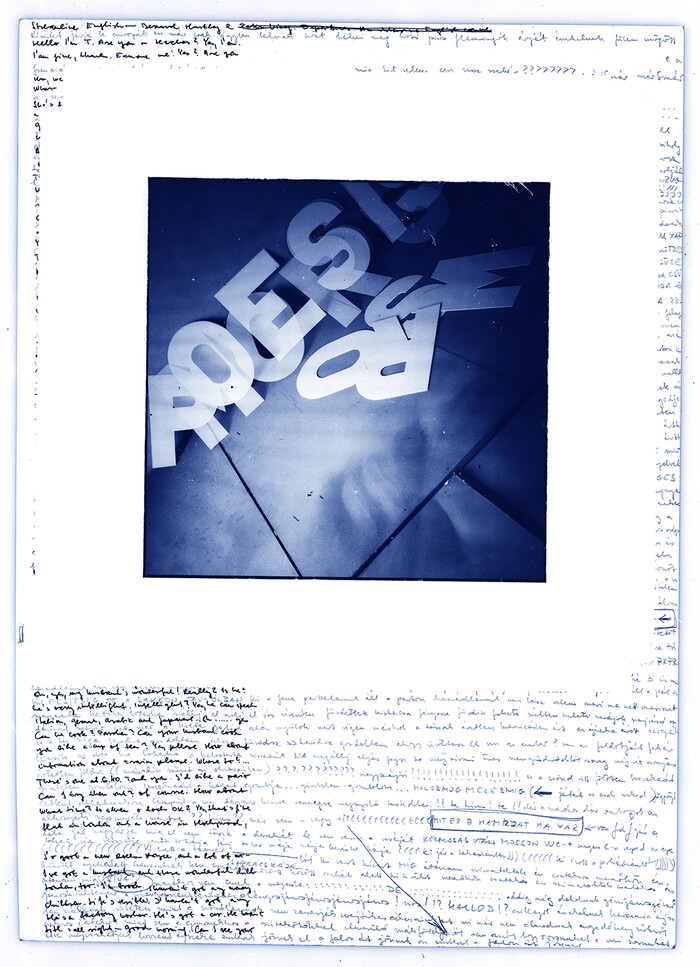

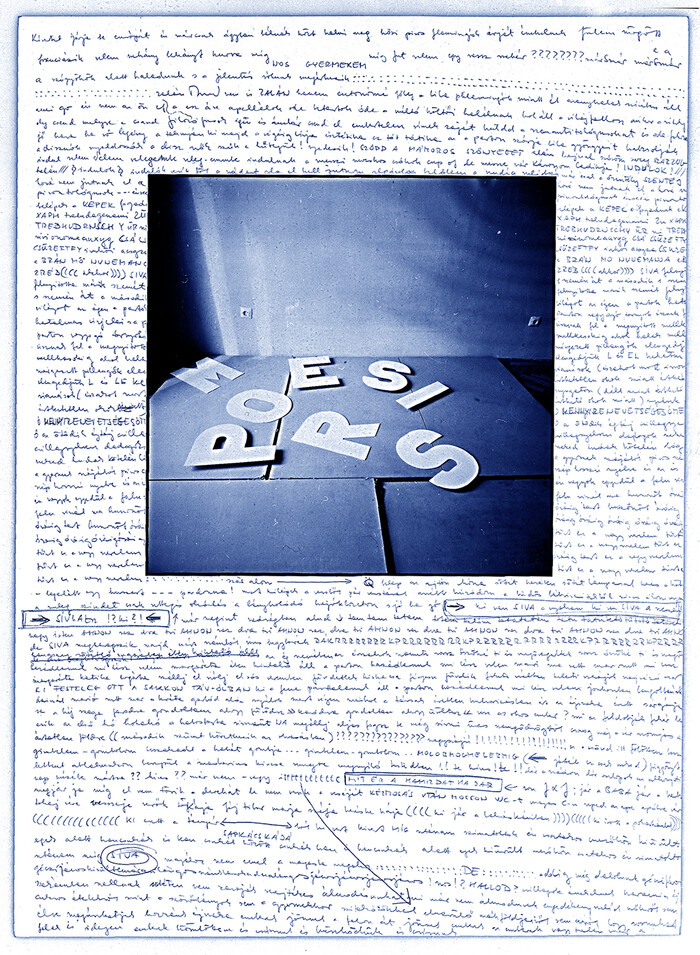

One time I was working for a longer period with László Török. He was cutting out the letters of two words from huge pieces of cardboard: POESIE - MORS. We started to work at the beginning of the week in his kitchen, and finished it at the end of the week, also in his kitchen. We started all our days in the same way in his kitchen and ended them there, too. We were drinking cold white wine mixed with cold soda water. We were having conversations firstly about art, secondly about world affairs, till the model arrived. Török led her into his studio (he has converted their biggest room into a studio), brought her a bathrobe and asked her to disrobe. In the meantime, we went out and drank again, talked about art again, and the secondary world. Sometimes this took us two hours. The naked model was waiting in the living room. In the end, Török made up his mind to stand up and walk into the living room to stand behind his ancient-looking photographing apparatus. I followed him. The model took off the bathrobe and stood or sat or lay down in front of the photographing machine according to the wishes of the young Master. Török was looking at her through the lenses for a prolonged time, then without taking any picture asked her to put on her clothes. We went out to the kitchen again, drank cold wine mixed with cold soda water again, and talked about arts and the secondary world. It took us another two hours to go back inside again. And the young Master didn’t take a picture, again. Another two hours in the kitchen. Then, finally, the click of the camera. Another two hours. Inside. Out. Another two hours... The day went by. The model put on her clothes and went home, and still we were sitting in the kitchen. I have no recollection whatsoever whether we had something to eat or not. As I don’t remember whether the model did or not. By the end of the week I’ve grown so accustomed to the presence of the strange female nude in our proximity that I haven’t even noticed her being there, as I wouldn’t have noticed her absence either. She was an object among other objects. It was that week when I came to understand Török. He didn’t even click his camera for ten times, I believe. And I didn’t even know that in reality work came after all this.

3.

For a longer period of time, it was the transparency and the interpretation of the phenomenon-word that was in the centre of Lászó Török’s attention, it was the reason he employed settings, it was the reason he created visual spaces, which he always modified by placing foreign (more foreign) objects in them, more often than not the light-signals of female bodies. However, there came a time when the ignorance of such „foreign presence“ became the objective of his artistic interest. This ignorance could have been achieved without putting the foreign object into the spaces he had created, but this would have meant the abandonment, or, more precisely, the renouncement of his artistic conception so far. Török chose a solution that was far more interesting: his technique is like the structural workings of our memory. In our mind, we create prints of the events that are either real or fictional. In the beginning, these prints are keenly accurate pictures of the static or dynamic events, but after a time, they fade and shift, nevertheless, they don’t disappear without a trace from our memory – this way they remain authentic. In the realm of light, transparency-phenomenon is the best tool to show this effect: the objects glimmer and shine through one another. Obviously, the underlying world manifests itself on the surface „closer“ to the observer by remaining still visible, however, its contours become uncertain, its materialistic being dissolves like in a dream or in a vision, but its existence and its possibility of existence cannot be denied. It is also possible that by this method Török is trying to capture the viewer’s perspective. Since these glimmering figures evolve by time into the signs of female bodies (in his early works, the female model was holding the translucent object either in her hands or in front of herself, and by doing this, creating the underlying space with her own body...) we must conclude that by assuming all this, we are getting closer to the essence of the photographer’s approach.

Nothing can be said with absolute certainty, of course, because – as it is the case with any worthwhile artistic concept – we are only allowed to formulate our speculations, or, incidentally, our doubts, but it out of the question to draw up an exclusive interpretation for the audience. What is certain, though, that the oeuvre that is outlined from this book and seems to have reached its final form (László Török is still living and is in good health, but, knowing his artistic attitude, we cannot expect that there will be any fundamental changes is his artistic world) is centred around an artist who is nothing but consistent in his artistic concept: we can follow a man’s – and an artist’s – walk of life by moving from picture to picture with the realisation that through time the alterations outline the artist’s face with the lines of permanency rather than with the lines of change.