Károly Kincses

Pictures of the Töröklét

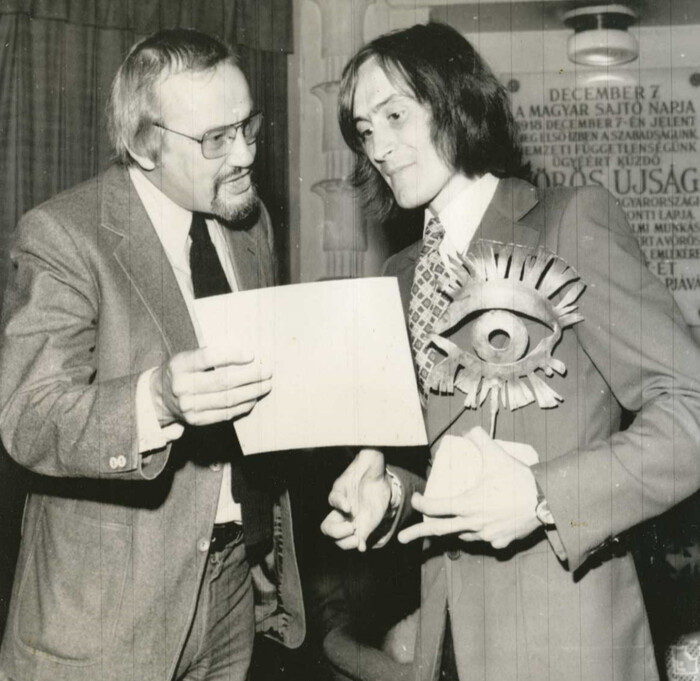

The World Press Photo’s Golden Eye Award had suddenly subverted the young photographer’s also very young career. His employer, the MTI dismissed him, and he was pronounced unsuited for making press photos... The year was 1973. Though all of this has cut Török to the quick, like it or not, fifty years later, considering his biography and oeuvre, we must admit that they were right. He would have never become a real photo reporter or press photographer that he has turned out to be if he had not been flung out from the so-called sanctuary of press photography, the MTI. It was better for Török, bearing in mind the long run, and not only for Török, but also for the complete Hungarian photography. After The Family, another picture of his was awarded by the WPP, called We Have No Time to Wait, and later that for all intents and purposes for almost half a century Török’s artistic career has continued up to the present day without any bigger flourishes or digressions. The ghost-like human beings (in most cases, female nudes) caused by the dissolves and the picture modifications, his partiality to the turnbull’s blue, the draperies, the weathering stones and walls all create a dreamlike, unrealistic scenery. All of this can be safely called the trademarks of Török as can his themes and titles that are both poetic and visual. Should we call it picture poetry? Or photo poetry? Indeed, we can, if one of the criteria is that the inner pictures of the artist which somehow materialize in his brain, in his soul find their homes both in a concrete and in a general sense. Török does not take a picture lightly. He ponders, thinks, talks, dreams a great deal, and after all this, the idea suddenly starts to materialize, then he chooses the model, searches for the location, plans the picture in advance, and after he has done all of this, he exposes for 1/125 seconds. So, what has just happened? Is the photograph really the art of the moment? After preparations that take weeks, sometimes months, the creative process takes only a tiny part of a second? I hope that you don’t think it is so. All Török’s pictures are the result of a long contemplation, part of a machine-less creation. His personal experiences are playing an important role in this process, but the people he has lived among and known are at least this important, who are mostly contemporary artists, principally poets. Tibor Zalán, Jenő Balaskó, Tibor Szervác, Endre Kukorelly, István Bella, Károly Bari, Gábor Cyprián Csajka, Károly Szikszay, Ákos Szilágyi and István Eörsi or Erzsébet Tóth has influenced Török both by their personalities and their poems. These poets have sometimes written about him, and Török has also created pictures titled like Quotation from Balaskó, Quotation from Kukorelly, and so on, but none of these artworks could be called illustrations. These pictures are not connected to the words written by the poets, but to the similar way they contemplate life, the similar understanding of the same things. They have the same sensitivity, they are both averse to the commercial, the expected and the required. They think the same things, they talk about the same things, but one uses the pen and the other uses the camera. This attitude is not usual in the history of the Hungarian photography. Török has also fought with this peculiarity when he started his career. It took many years for others to accept that he uses this language and “talks” like this and “says” things like this. Then everybody has acquiesced. As of today, Török has got into the Hungarian photography’s Hall of Fame, has become a point of reference, is part of the language of photography, and he who has always abhorred to follow anybody, became somebody to follow. To make this following somewhat more difficult, he has moved away from the capital, removed himself from the bustle and self-positioning. He, who has been an important participant in the life of the Hungarian photography by founding the Pajta Gallery, leading the First Constructive Group and organizing exhibitions, book editions, film screenings, summer workshops, nowadays spends most of his time sitting on the porch of his thatched house at Salföld, leaning against the glass wall of the Pajta Gallery, smoking the day away, conversing and hobnobbing. He has found his place and he is also found by those who have something to do with him, who want to know his secret or simply are drawn to the lifestyle chosen by Török.

It is not sure that the viewer thinks the same and thinks the same way contemplating Török’s quotations. In the end, all situations in an exhibition are a two-way interaction between the picture and its viewer. Undoubtedly it is important what the author shows and how he does it, the title of the picture is important, the work of the curator is important, how the picture is displayed, in what situation, how big it is, what the context is, it is important what the viewers standing next to me say, whatever part of a conversation I catch...All of the above and a thousand more things count. But the most essential thing is that when you and the picture are alone, gauge the adequate distance in order to create the intimate place between you and the picture: after all of this, you can start to see, feel, think anything... Creating the personal conversation between the picture and the viewer is the essence and basic goal of any exhibition. Surely there are exhibitions and pictures in excess that don’t implement this objective for whatever reason, but this cannot be said about Török’s pictures and their displays. However, since his literally inspired pictures are not simply the illustrations of the poems or demonstrate the poets as portraits, but are poetical and unrealistic on their own account, interpreting them is not an easy task. All of us must involve our own personalities to solve the mysteries of Török’s artistic world. It is not always trivial, but who has ever said that deciphering the message of an exhibition is simple. Perhaps the fact that Török though somewhat monomaniacally always says the same, the ensuing artistic periods can be identified very clearly: the oeuvre is built of these.

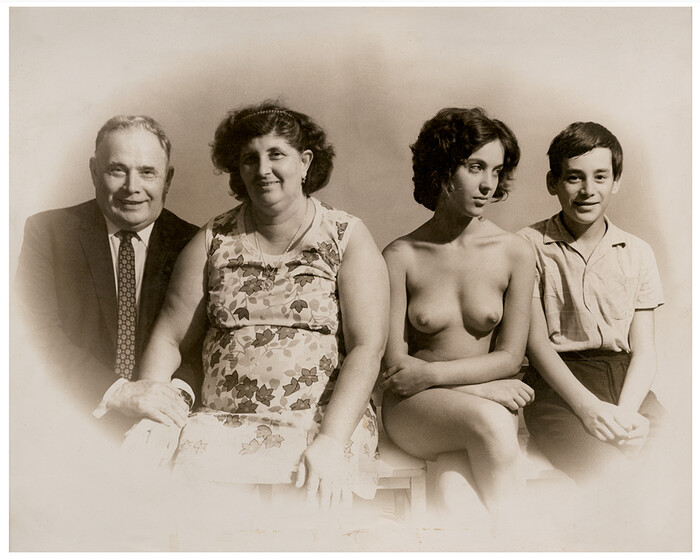

THE FAMILY

His early pictures that started his artistic photographic career are more ironic and rooted in gag than are based on visual effect. Then came success and acknowledgement that defined and determined his life. The young man experienced both the advantages and the drawbacks of success. As I have mentioned before, in 1972 his world exploded when he received the Golden Eye Award of the World Press Photo. This picture has determined his fate and made the relationship between Török and the photography final. Whatever he gained, he seemed to have lost, too, since the contemporary cultural policy regarded his success as a treason against the socialist ideal of family instead of an artistic one.

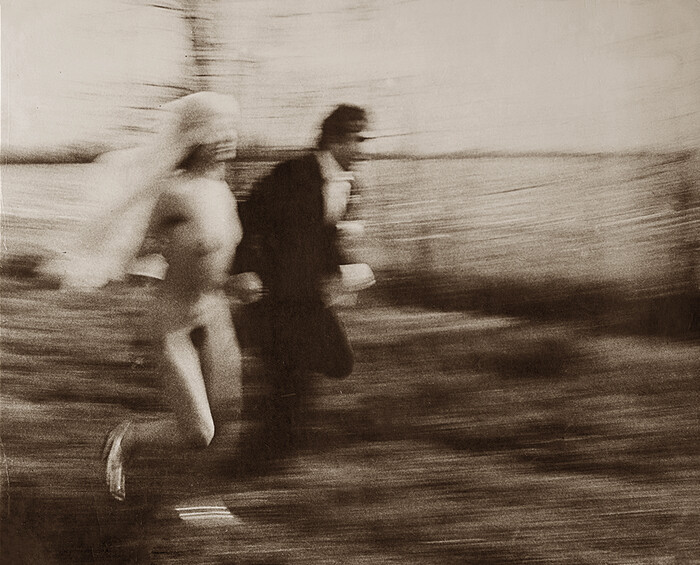

The Family was followed by his other early pictures that also gained success: We Have No Time to Wait (1973), Wobbler Train (1977), In memoriam of a camera (1977), After the Concert (1976) and the other striking and intricate photos based on strong ideas that are precisely transmitted through his art. After a while, Török noticed that the directness and the fact that they can be easily read obscured and overwrote everything that he wanted at that time: that his photos could mean more than the visual experience, so he can achieve his desired affect through more iconic and less direct effects. “So, this was the starting point, and the award lent me a sort of self-confidence to relate my thoughts about photography to this achievement...” (25 év. Beszélgetés Török Lászlóval by Gabriella Megyesy. In: Szellemkép, 1998. 2-3., p. 39.) He continued his way on the path he has chosen.

ALTERATIONS

“I started to ponder how to reduce the punchline part of photography to formulate my thoughts the simplest way possible, like pictograms. These pictures in my book titled Alterations are seem to be more clear-out.” (Fotográfiai alkotóműhelyek: Pajta Galéria – Beszélgetés Török Lászlóval by Sándor Bacskai. In: Fotóművészet, 1996/5-6., p. 3.) The first embodiment of this trend was the series titled In Memoriam of an Ant in 1977 based on the poem by István Bella titled Halotti beszéd. Consequently, after finding the aforementioned forms of display, many photos, pairs of photos and triptychs were realized, which were presented under the title Alterations at the Helikon Gallery of the Műcsarnok at Budapest in 1983. These photographs were brown and blue monochromic artworks already, which appeared in a book, in the 4th part of the JAK Füzetek published by the Young Poets’ Attila József Circle as a photographic publication in the same year. Its preface was written by Tibor Zalán. “The everyday pictures that underwent the alteration seem to be beyond the reality, to float in a dreamlike state and associative in a surrealist way when they are put back into their ordinary surroundings. Principally, Török composes the reality and not the photograph he made. Instead of portrayal, expression becomes authoritative. He works only with settings... László Török is an overly characteristic artist. He puts his life on the line for one a manically repeated gesture whichever themes he undertakes. In fact, this gesture is his only theme. He keeps reiterating the same thing from his first picture to his last.” All of this paved his way to the meeting with Károly Bari and the commencement of their joint work.

GYPSIES

Török accompanied Bari on his trips throughout the country and Transylvania where Bari recorded the remaining memories, imprints of the traditional Gypsy culture. In turn, Török took photographs, but he did not use the topics the previous photographers employed in similar positions. Instead of taking sociographically documentary photos, he approached the essential with the by then largely established and well-practiced means of abstract description. The photographs that appeared both in the exhibition titled Gypsies and in printed forms (in catalogues and on the pages of magazines) spoke in the language of Török about very serious matters: the perseverance and integration of an ethnical group that has a different culture, has different roots and leads a different lifestyle, how it accepts its merits, and also about its assimilation. By using many formal effects, he achieved that his pictures show the phenomenon and not the things they depict. The life-sized photographs on the pictures themselves (the effect is called picture in the picture) became important tools, as are the out of focus, ghost-like human forms generated by the double expositions. The presence of the white shrouds at the locations resulted in a metaphoric read. Unlike the black and white shots used mainly by the documentary photographers or the full colour photographs appearing in reports, he chose a specific cyanic blue for himself, so he put even more emphasis on his intentions: by using this monochromic setting he could abstract his subjects from the realistic objectivity and move them to the artistic objectivity.

Not only he created a photographic cycle that does not age, but he also appointed the road for himself, the road that he has never really left since. His works are previously conceived ideas that are realized in photographs later, often months or even years pass between the idea and its realization. Török has answered the following when questioned by Mihály Gera concerning the origins of the pictures: “My photographs are not snapshots. I live through situations that I try to reconstruct afterwards.” (Quoted by Mihály Gera in his article titled Cigányok. In: Új Tükör, 12/12/82.)

Taking all of this into account, Gera recreates closely the artistic methods of Török when he analyses the material of the exhibition titled Gypsies. “He searched for motifs to describe the situations he lived in. Rugged trees, parts of a street, tumble-down adobes, interiors, then he placed in the dimension of the picture a snow-white shroud, or the enormously magnified copy of a photo taken in the same place, or perhaps he mashed together these parts. The result is astonishing: the picture suggests the actuality. The recurring motifs grow to be symbols. The participants, on the other hand, while present their substance, also show the eternal signs of a fate that can be generalized. The effect of the awe-inspiringly beautiful and deeply humane photographs is not instantaneous.” (Cigányok by Mihály Gera. In: Új Tükör, 12/12/82.)

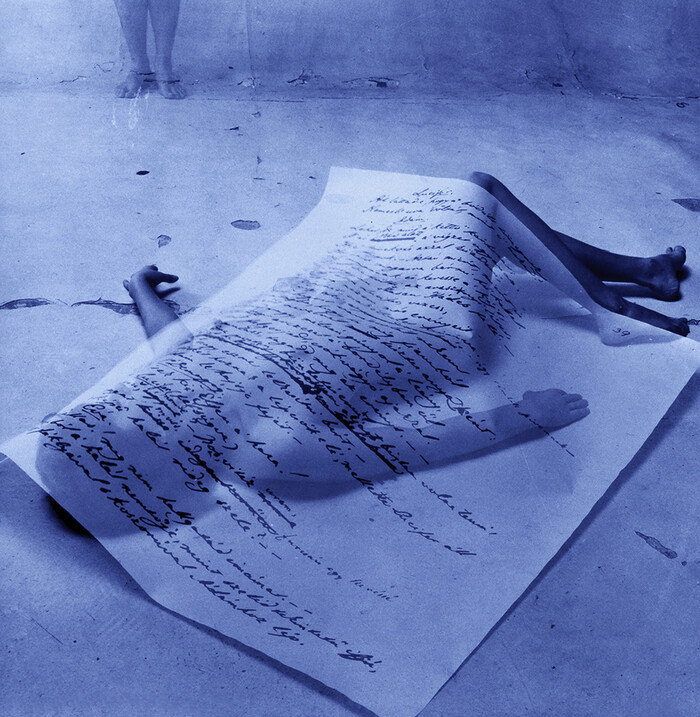

QUOTATIONS

The systematic building of the oeuvre continued. From here, the Török of the era of Modifications turned his attention to the Quotations, which pictures reflect both to the living and dead authors of the Hungarian literature and their hand-picked pieces. Here we find the whole photographic arsenal that is specific to Török. What does it contain? I count it all out. He mostly creates monochromic pictures, their colours mainly blue, sometimes brown. The twice or three-time expositions or the out of focus technique become the trademark of Török. The montage. The frequent usage of the female nude. The application of shrouds and wrinkled backgrounds. Have I left something out? Maybe the emphatic use of the chiaroscuro. He organized an exhibition in reduced colours in 1986 at the Fotóművészeti Galéria at Váci Street concentrating on his poet acquaintances and friends titled Quotations. By this stage of his career, what he had planned and already been doing for a while has crystallised out: forging a connection between two different types of art, to make a strong connection between the written poetic picture and the picture created by light.

And the pictures, inspired by a word, an idea, a poem, sooner or later became poems embodied in a photograph. Most of the time, later. Later, because he has contemplated all his pictures for a long time, he has drawn sketches, made careful selections from the best of models who gave their bodies to realize the poetic idea two-fold: both in words and in pictures. I quote Tibor Zalán again: “...There are two permanent participants on their photos, the female nude and the wrinkled drapery that symbolizes the space... The artist doesn’t trust in the self-organizing principle of nature. In his photographic moments, there are no natural settings, because the signs, the natural signs themselves lose their sincerity, more specifically their self-meaning... Therefore, Török begins from the other side, from the side of the signs reduced to themselves. He chooses a sign. His first and foremost and exclusive sign is the female nude... The photograph suspends the surroundings, too, the reality which seems to be real changes places with the engineered reality, which seems to be irreal.” (A lényeg mindig meztelen. In: Élet és Irodalom, 19/03/1982)

ANZIX FROM SALFÖLD

Török László’s oeuvre’s heretofore last period that continues to the present is produced in Salföld. When in 1991 he received the Kodak Award in Düsseldorf, to fill in the hiatus caused by the sudden closure of the Fotóművészeti Galéria, he decided to open a place suitable for exhibitions by rebuilding the barn next to his already existing farmhouse in an enchanted little village, Salföld, situated in the Káli basin. The Pajta Galéria (i.e. Barn Gallery) has been in operation continuously since June 1991. Since its foundation, in the last nearly three decades the Pajta Gallery has become an important place for the Hungarian progressive photography. Almost forty artists are connected to the Gallery by their work, and it presented more than a hundred photographs on its walls. But this is only one side of the coin relating to his existence in Salföld. Török has organized nurseries for artists here, giving the chance to many artists to create artworks in this tiny village and its surroundings. He himself has taken and still takes many photos here, acting up to his own principles undertaken by his own volition, creating connections and symbols between the young female nudes and the old buildings, walls, places formed by the lapsing time by presenting them both on the same picture. Now, he stands here, but as far as I know him, he doesn’t stop here, he moves forward by working continuously.

QUOTATIONS FOR THE PAGES WITH PICTURES

Undoubtedly, it is important what the art critics, journalists, photo historians write about Török’s artwork, but let us take a look at what do those people think who are evoked by him on his pictures or by the titles of his works, on the off chance that maybe a different dialogue is born from this interaction between the photographer’s photos and the writers’ writings beyond the usual ones.